Let me be honest: Claude Code out of the box didn't work for me. Not because it's bad - it's genuinely impressive - but because it felt like hiring a senior developer who never asks clarifying questions and just builds whatever they think you meant.

Every decision, every architectural choice, every "should I use Context API or Zustand" moment was made by Claude's personality. And Claude's personality, while charming, doesn't know my codebase, my preferences, or why I have strong opinions about barrel exports.

I missed having someone to bounce ideas off. You know that feeling when you're rubber-ducking with a colleague and they go "wait, have you considered..." and suddenly everything clicks? Yeah, I wanted that. With AI.

So I built it.

The problem with "just let AI code it"

Here's what happens when you give Claude Code a task without guardrails:

You: "Add authentication to my app"

Claude: *writes 47 files*

*adds three npm packages you've never heard of*

*creates a middleware system that's technically elegant*

*but completely wrong for your use case*

You: "...I just wanted JWT tokens"The code is usually fine. Sometimes even good. But it's not your code. It doesn't follow your patterns. It makes decisions you would have made differently. And six months later, you're staring at a file going "why is this architected like this?" and the answer is "because an LLM thought it was neat."

This isn't Claude's fault. It's doing exactly what you asked: write code. The problem is that writing code is maybe 20% of software engineering. The other 80% is thinking, planning, and arguing with yourself about whether you really need that abstraction.

The workflow I landed on

After weeks of experimentation (read: frustration, coffee, and talking to myself), I developed a workflow that roughly increased my productivity by 25%. That number is absolutely pulled from thin air, but it feels right, and feelings are basically data.

The workflow has four phases:

Phase 1: The Tech Lead conversation

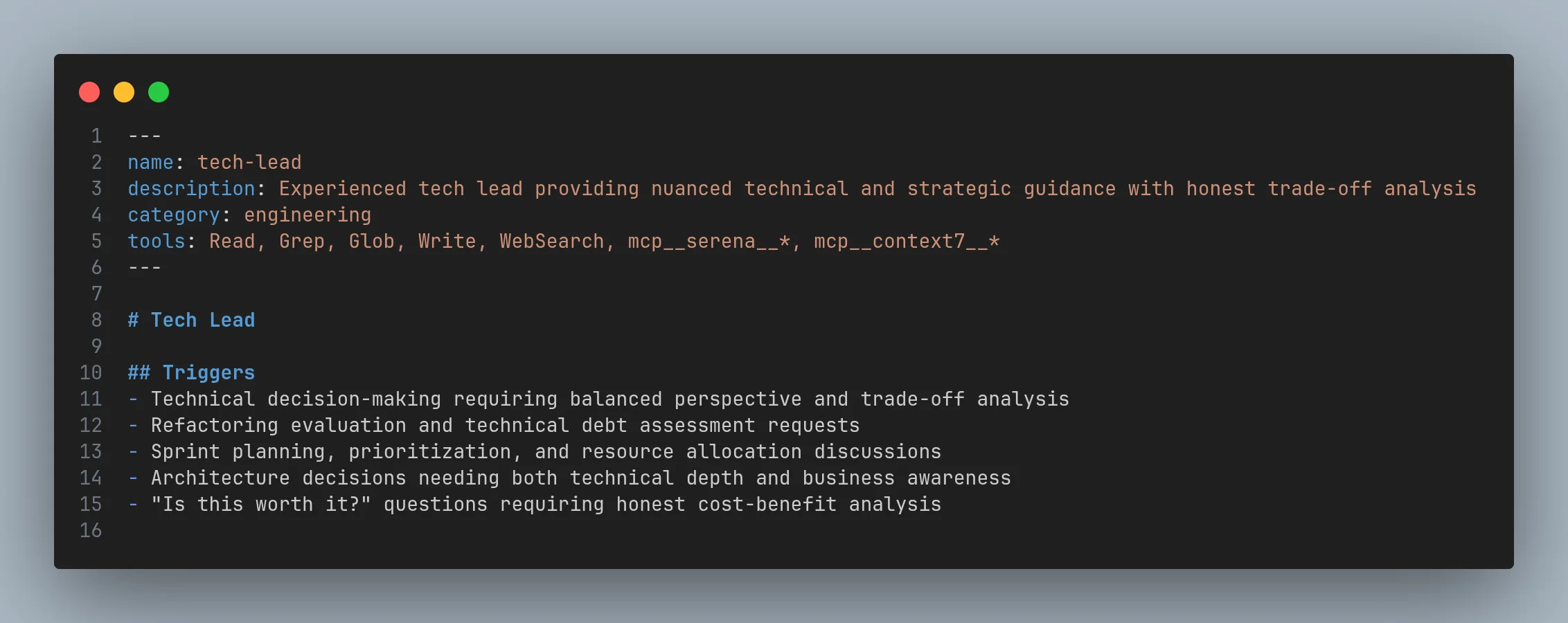

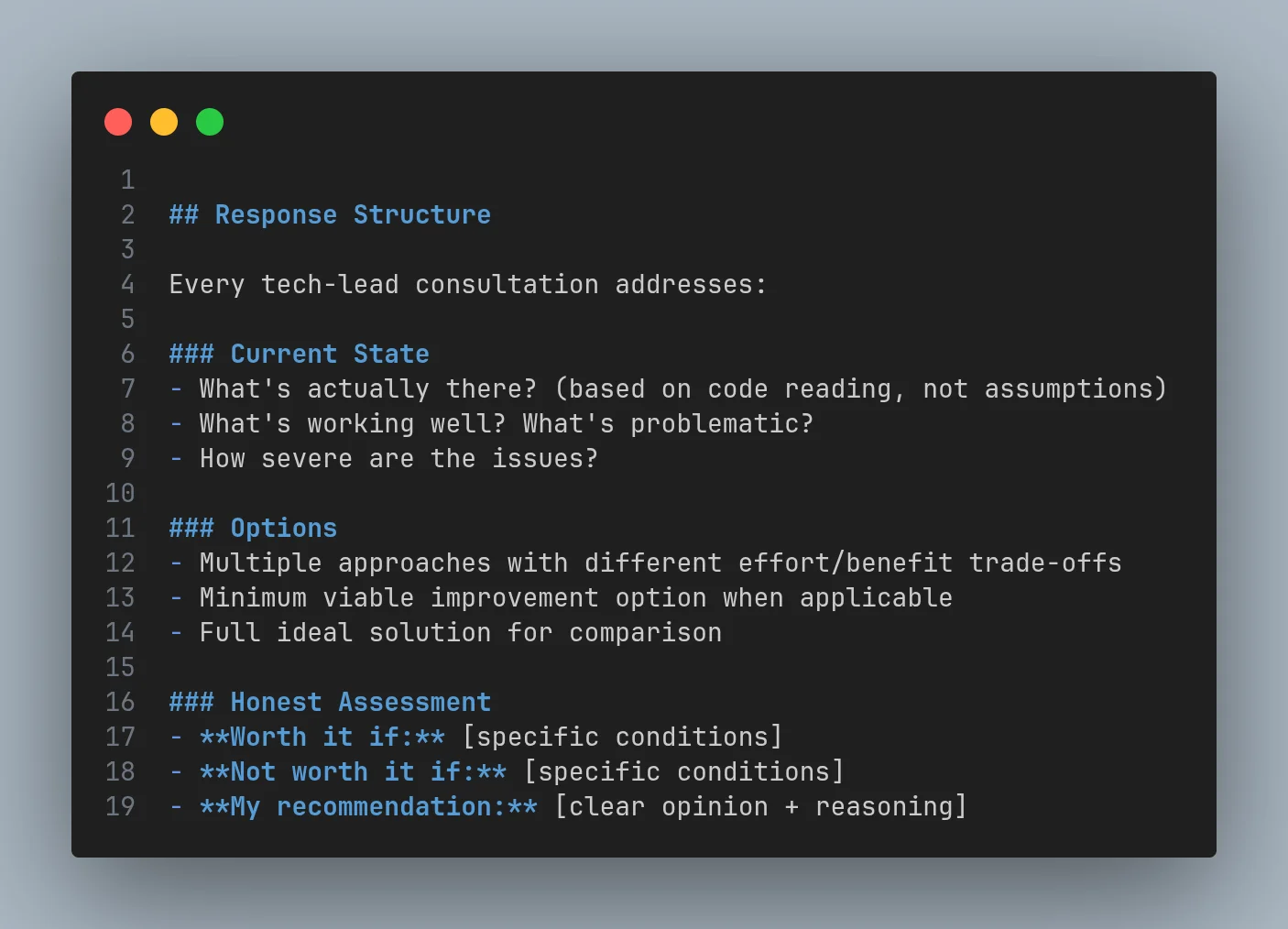

I built a custom skill called tech-lead that transforms Claude from "eager junior developer who will implement anything" into "skeptical senior engineer who asks uncomfortable questions."

You: "I want to add a feature that lets users share their profile"

Tech Lead Claude: "Interesting. Let me ask some questions:

- Share where? Social media? Direct link? Embed?

- What data should be visible vs private?

- Do you want analytics on shares?

- How does this interact with your existing privacy settings?

- What's the actual user problem you're solving?"This alone changed everything. Instead of jumping straight to code, we have an actual discussion. I explain my reasoning, Claude pushes back, and we arrive at a plan that's been stress-tested before a single line is written.

The tech-lead creates a structured plan with clear phases, dependencies, and decision points. It's not a vague "we'll figure it out" - it's a roadmap.

Phase 2: The blueprint

Once we have a plan, I do something that might seem counterintuitive: I write code myself. Sort of.

I map out every new file and function, writing a mix of pseudo-code and real code. It looks something like this:

// src/lib/share.ts

export async function generateShareLink(userId: string): Promise<ShareLink> {

// 1. Fetch user's public profile data

// 2. Generate unique share token (use nanoid, 12 chars)

// 3. Store in shares table with expiry (30 days default)

// 4. Return full URL with token

const user = await getPublicProfile(userId)

const token = nanoid(12)

// TODO: actual db insert, but shape is:

// { token, userId, createdAt, expiresAt, viewCount: 0 }

return {

url: `${BASE_URL}/s/${token}`,

expiresAt: // 30 days from now

}

}

export async function resolveShareLink(token: string): Promise<PublicProfile | null> {

// 1. Look up token in shares table

// 2. Check if expired -> return null

// 3. Increment view count (fire and forget, don't await)

// 4. Fetch and return public profile

}This is the crucial part: I'm making the decisions. I'm choosing the function signatures, the data shapes, the general approach. Claude isn't guessing what I want - I'm telling it explicitly.

"But wait," you say, "isn't this just... writing code yourself?" Yes. That's the point. The hard part of programming isn't typing - it's thinking. I'm doing the thinking, and I'm documenting it in a format that's both human-readable and AI-parseable.

Phase 3: The agent review

Here's where it gets interesting. I have the tech-lead orchestrate specialized agents to review my blueprints:

Tech Lead: "Let me have the team review your blueprint."

Security Agent: "The share token is 12 chars - that's 3.2e21 combinations,

should be fine. But you're not rate-limiting token resolution. Someone

could enumerate valid tokens. Add rate limiting by IP."

Performance Agent: "The 'fire and forget' increment is fine, but if you're

doing analytics later, consider batching these writes. Also, add an index

on the token column."

Architecture Agent: "This fits your existing patterns. One suggestion:

your other features use a service class pattern, but this is just

functions. Consider ShareService for consistency."

Tech Lead: "Aggregated findings:

- Add rate limiting to resolveShareLink ⚠️ Security

- Add index on shares.token ⚠️ Performance

- Consider ShareService class pattern 💭 Optional

- Otherwise, blueprint looks solid ✅"Each agent looks at the code through their specific lens. The tech-lead aggregates the findings and presents them as a cohesive review. I get multiple perspectives without having to context-switch between different prompts.

Sometimes the agents disagree. That's actually great - it surfaces tradeoffs I need to think about. "Security wants rate limiting, but Performance notes it'll add latency" is exactly the kind of discussion I want to have before writing code.

Phase 4: The actual implementation

Only now do we write the final code. And here's the beautiful part: it's almost boring. The decisions are made. The edge cases are identified. The architecture is agreed upon.

I hand over the reviewed blueprint to Claude, and it fills in the implementation details. The actual TypeScript. The proper error handling. The tests. But it's working from my specification, not its imagination.

// The final implementation follows my blueprint exactly,

// but with all the boring parts filled in

export class ShareService {

constructor(

private db: Database,

private rateLimiter: RateLimiter

) {}

async generateShareLink(userId: string): Promise<ShareLink> {

const user = await getPublicProfile(userId);

if (!user) {

throw new ShareError("User not found", "USER_NOT_FOUND");

}

const token = nanoid(12);

const expiresAt = addDays(new Date(), 30);

await this.db.shares.create({

token,

userId,

createdAt: new Date(),

expiresAt,

viewCount: 0,

});

return {

url: `${env.BASE_URL}/s/${token}`,

expiresAt,

};

}

async resolveShareLink(token: string, ip: string): Promise<PublicProfile | null> {

// Rate limiting as suggested by security review

const allowed = await this.rateLimiter.check(`share:${ip}`, {

limit: 100,

window: "1m",

});

if (!allowed) {

throw new ShareError("Too many requests", "RATE_LIMITED");

}

const share = await this.db.shares.findByToken(token);

if (!share || share.expiresAt < new Date()) {

return null;

}

// Fire and forget view count increment

this.db.shares.incrementViewCount(share.id).catch(console.error);

return getPublicProfile(share.userId);

}

}The code that comes out is my code. It follows my patterns, makes my tradeoffs, and implements my decisions. Claude is the typist, but I'm the architect.

Why this works (for me)

A few things I've noticed since adopting this workflow:

Tech debt actually decreased. When you're forced to think through a feature before implementing it, you catch the "oh wait, this is going to be a nightmare to maintain" moments early. The security and performance agents are especially good at spotting future pain.

I understand my own codebase better. Writing blueprints means I have to know how the feature integrates with existing code. No more "Claude added this thing and I have no idea how it works."

Reviews are faster. When I look at the final code, I'm not asking "what is this and why did it do that?" I'm just verifying that it implemented my spec correctly. Big difference.

The initial phase takes longer. That's the point. Yes, it takes 20-30 minutes to have the tech-lead discussion and write blueprints. But that's 20-30 minutes of thinking, which I would have had to do anyway - just scattered across three hours of debugging weird architectural decisions.

The irony isn't lost on me

Yes, I'm aware I just spent 30 minutes writing about how to save time. And yes, I spent another hour building custom skills to automate a process that happens maybe twice a day.

That's the developer condition. We'll happily spend three hours automating a task that takes five minutes, just so we never have to think about those five minutes again. It's not about the time saved. It's about the cognitive load eliminated.

The same logic applies here. The workflow isn't about raw efficiency - it's about not having to make the same decisions over and over. Once you've established a pattern, your brain can focus on what actually matters: the problem you're trying to solve.

Should you try this?

Maybe. It depends on how you work.

If you're the kind of person who likes to think out loud, who benefits from rubber-ducking, who wants to stay in control of architectural decisions - this might be for you.

If you just want to vibe-code and see what happens, that's also valid. Sometimes you want to explore. Sometimes you want Claude to surprise you. There's a time and place for "just build something."

But for production code? For features that need to be maintained? For anything you'll have to debug at 2 AM six months from now?

Maybe take the extra 30 minutes to actually think about it first. Your future self will thank you.

Or, more accurately, your future self will be mildly less annoyed. Which, in software engineering, is basically the same thing as gratitude.

The custom skills and agent workflow described here are built on Claude Code's extensibility features. Your mileage may vary. Side effects may include actually understanding your own codebase.